Hubble’s planetary portrait captures changes in Jupiter’s Great Red Spot

13 October 2015

Scientists using the NASA/ESA Hubble

Space Telescope have produced new maps of Jupiter that show the

continuing changes in its famous Great Red Spot. The images also reveal a

rare wave structure in the planet’s atmosphere that has not been seen

for decades. The new image is the first in a series of annual portraits

of the Solar System’s outer planets, which will give us new glimpses of

these remote worlds, and help scientists to study how they change over

time.

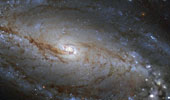

In this new image of

Jupiter

a broad range of features has been captured, including winds, clouds

and storms. The scientists behind the new images took pictures of

Jupiter using Hubble’s

Wide Field Camera 3

over a ten-hour period and have produced two maps of the entire planet

from the observations. These maps make it possible to determine the

speeds of Jupiter’s winds, to identify different phenomena in its

atmosphere and to track changes in its most famous features.

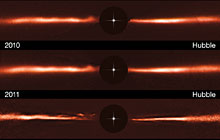

The new images confirm that the huge storm, which has raged on

Jupiter’s surface for at least three hundred years, continues to shrink,

but that it may not go out without a fight. The storm, known as the

Great Red Spot,

is seen here swirling at the centre of the image of the planet. It has

been decreasing in size at a noticeably faster rate from year to year

for some time. But now, the rate of shrinkage seems to be slowing again,

even though the spot is still about 240 kilometres smaller than it was

in 2014.

The spot’s size is not the only change that has been captured by

Hubble. At the centre of the spot, which is less intense in colour than

it once was, an unusual wispy filament can be seen spanning almost the

entire width of the vortex. This filamentary streamer rotates and twists

throughout the ten-hour span of the Great Red Spot image sequence,

distorted by winds that are blowing at 540 kilometres per hour.

There is another feature of interest in this new view of our giant

neighbour. Just north of the planet’s equator, researchers have found a

rare wave structure, of a type that has been spotted on the planet only

once before, decades ago by the Voyager 2 mission, which was launched in

1977. In the

Voyager 2

images the wave was barely visible and astronomers began to think its

appearance was a fluke, as nothing like it has been seen since, until

now.

The current wave was found in a region dotted with cyclones and anticyclones. Similar waves — called

baroclinic waves — sometimes appear in the Earth’s atmosphere where

cyclones

are forming. The wave may originate in a clear layer beneath the

clouds, only becoming visible when it propagates up into the cloud deck,

according to the researchers.

The observations of Jupiter form part of the Outer Planet Atmospheres

Legacy (OPAL) programme, which will allow Hubble to dedicate time each

year to observing the outer planets. In addition to Jupiter,

Neptune and

Uranus have already been observed as part of the programme and maps of these planets will be placed in the public archive.

Saturn

will be added to the series later. The collection of maps that will be

built up over time will help scientists not only to understand the

atmospheres of giant planets in the Solar System, but also the

atmospheres of our own planet and of the planets that are being

discovered around other stars.

Notes

The findings are described in an

Astrophysical Journal paper First results from the Hubble OPAL program: Jupiter in 2015, available online.

Notes for editors

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between ESA and NASA.

More information

Image credit: NASA, ESA, A. Simon (GSFC), M. Wong (UC Berkeley), and G. Orton (JPL-Caltech)

Links